REVIEW by David DeBoor Canfield

The roots of speech music go back at least to Alexander Dargomyzhsky in mid 19th-century Russia, the genre of the late 19th-century melodrama, and the use of Sprechstimme by composers such as Humperdinck and Schoenberg, but Harry Partch may fairly be said to have brought the form into full flower. Partch developed the genre to an amazing degree, even to the point of creating a whole new battery of instruments, and an entirely new system of tuning to accompany his intoned speech. In his music, composer William Vollinger continues the tradition of Partch, but has built his own distinctive style involving only traditional instruments in standard tuning.

Vollinger succinctly sums up his musical aesthetic in the liner notes of the present CD: “There are two basic things I want to do when I compose: (1) explore new territory, and (2) say something good about the human condition, even when funny.” It is safe to say that he succeeds in both of these goals, not only in these two works, but in others that I’ve heard by him. Indeed, his music is original in the best sense of the word in that for every work I’ve heard by him, my reaction has always been, “No one else could have written that!” His music is defined by urbane wit, poignant texts (invariably of his own composition), a declaimed vocal style that falls somewhere in between measured speech and Sprechstimme (and occasional singing), all of which is accompanied by instrumental figures and textures that reinforce and underscore the texts in well-thought-out ways.

I first got to know his music back in the LP era, when I encountered his More than Conquerors on the Grenadilla label. This work is a touching depiction of the life of Corrie ten Boom, famous for her work in hiding and thus saving the lives of many Jews in Holland during World War II.

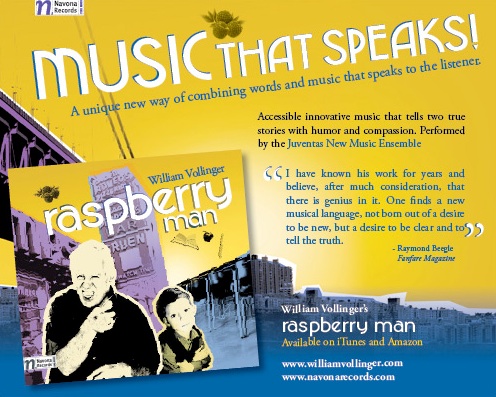

The first work on the present CD is Raspberry Man, a real-life story in music about a colorful character of the sort that New York seems to be famous for. This fellow, name unrevealed, achieved his reputation (and epithet) by standing outside Jack Dempsey’s restaurant in Manhattan, sticking out his tongue at passersby and giving them Bronx cheers. These are represented quite onomatomusically (if I may coin a term) by the instrumental ensemble. At the end of the work, the narrator is left wondering what ever became of the man. Was his dying breath, perhaps, expended in a Bronx cheer?

Emmanuel Changed is also a true story about a former student in Vollinger’s children’s choir. The young man changed over a summer from being a friendless, bullying 10-year-old hellion, to a decent young lad who eventually gained some friends. It is a touching piece, full of gentle humor. Vollinger imaginatively uses his sparse forces (an alto sax and piano) to musically underscore the transformation of this young boy.

Both of these works, along with the other music by Vollinger I’ve heard, spring out of his Christian faith, a faith that to Vollinger necessarily produces fruit—often expressed in terms of compassion toward one’s fellow man. His is music with a message—not always explicitly Christian, but always seeking to elevate the thoughts and actions of the listener to a higher plane. In this, he succeeds admirably on both musical and spiritual grounds.

The prospective purchaser should note that there are only about 12 minutes of music on this CD, the remainder of which is given over to files that can be accessed on one’s computer. These include an interesting video containing an interview with the composer, during the course of which he discusses his philosophy of composition, and his ideas about originality. There is also a live video performance of Raspberry Man, scores of both of the works on the CD, and (apparently) downloadable ring tones. I didn’t try those out (I gave up my ring tone of “The Great Gate of Kiev” that I had for a long time in favor of the kind of ding-a-ling ring that phones had when I was a kid), but everything else that I tried on the computer portion of the CD worked well.

Performances by the unnamed narrator and the Juventas Ensemble are first-rate. Not everyone I know is fond of speech music, but those who are will find much to admire in this finely produced disc. Accordingly, highly recommended.

(The above article originally appeared in Issue 35:3 (Jan/Feb 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.)

REVIEW by Raymond Beegle

Most first-graders in U.S. schools are told that America is the great melting pot. In subsequent years, they learn by observation and experience that many elements in that pot are slow to melt, or not prone to melting at all. From the musical standpoint, things were simple enough at our beginnings. In colonial times and well through the 19th century Americans generally mirrored European traditions, producing some competent composers who imitated the styles of their European contemporaries. So-called popular music did not exist, as Stephen Foster and his kind were really rustic Schuberts, writing charming melodies and lyrics on the romantic themes of the day. However, political and social upheavals as well as technological advances changed all of this, and in less than 150 years American culture became a shattered mirror whose fragments reflect a chaotic jumble of tastes, values, and forms. The rise of popular culture has given us jingles, jazz, blues, torch songs, mood music, Muzak, rock, rap, musicals, movie scores. Serious music has broken traditional ranks, spawning a plethora of new schools that sometimes exclude melodic line, harmony, or comprehensible rhythmic patterns. The 12-tone system, Minimalism, electronic music, and Cage’s idea that “music is organized sound,” which introduced vacuum cleaners and airplane motors to the concert stage, have created a Tower of Babel in which there is no commonly understood language.

Many disparate elements from both categories, however, fall into a happy and unifying alliance in William Vollinger’s two compositions on this CD. From the more traditional standpoint, the vocal writing, albeit not precisely what Schoenberg would regard as Sprechstimme, is nonetheless a similarly stylized inflection of the text’s rhythm and nuance. As well, one can find similarities to Poulenc’s Le Bestiaire, although Vollinger’s sophisticated and sometimes complex instrumental writing is more fragmented in its coloring and underscoring of significant words. Poulenc generally has the singer’s melodic line and rhythm doubled by an instrument, whereas Vollinger’s narrator keeps the rhythmic element and omits the melodic entirely. It is very curious to find that his words flow in easy sequence whereas his music, in direct contrast to Poulenc’s, moves from phrase to phrase, even measure to measure in a desultory fashion: a musical vertical to the word’s horizontal. Although Schoenberg, Poulenc, and finally Gioacchino Rossini may seem an odd lineup of traditional references, I would like to call the Italian maestro as witness for the defense, in case the listener sees no traditional grounds for the Raspberry Man’s often repeated expletive. Rossini’s jolly little babe in Chanson de Bébé is just as crude and repetitive with his “pipi-caca” (the reader may translate from the French for himself) as William Vollinger’s strange protagonist.

In regard to the world of pop culture, Emmanuel Changed and especially Raspberry Man are unapologetically filled with the bells and whistles of trendy radio and television music reminiscent of cartoon soundtracks and toy commercials. Also, when there is extended melodic material and a line or two is actually sung, it is in the Sondheim style, often with the music-box piano arpeggios he constantly used.

As the narrator is William Vollinger himself, we are saved the difficult assignment of guessing whether the artist is carrying out the wishes of the composer. Vollinger takes great joy in performing the role of a good-natured Sunday school teacher, simplifying life’s most profound moral lessons, and sometimes imitating, as teachers of the young often do, the students’ manner of speaking.

Congratulations are due the first-class members of the Juventas Ensemble, who play with virtuosity, expressive tone, and an outstanding rhythmic accuracy as they shadow every move the narrator makes. No easy task!

Congratulations are also due the technical engineers, who produced a warm ambient acoustic, making the words crystal-clear, and subtly highlighting the many instrumental effects that pepper both pieces.

Dominating both of these works, making its presence felt in every note, every word, is William Vollinger’s message. To miss it is well-nigh impossible. One has the sense that the composer would sacrifice any musical or literary canon, employ any artistic device, to convey the message. Words take precedence over music, but the message itself seems to have forcefully determined the style and shape of these compositions. Clarity is center stage. Although much serious music of our time demands copious program notes to explain what the composer has failed to convey through his work, it is not the case here. There is nothing to be explained, only felt, and whether one is pleased or displeased with the eccentric mix of idioms, the message is clear; it is tempting to say, loud and clear! One is deeply moved: music’s ultimate goal. Perhaps the how and why of it is a very private matter, between the composer and his muse.

(The above article originally appeared in Issue 35:3 (Jan/Feb 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.)

GAPPLEGATE CLASSICAL-MODERN MUSIC REVIEW

by Grego Applegate Edwards Friday, February 17, 2012 classicalmodernmusic.blogspot.com

Schoenberg's "Pierrot Lunaire" brought the art of sprechstimme into the vocabulary of new music.

Speech-song stays with us in various ways. One highly idiomatic and funny way is with William

Vollinger's Raspberry Man (Navona 5857), a short ten minute, two work single CD.

The title work is a chamber piece for small group and singer-recitator. The composer does the vocal

part; the Juventas Ensemble takes on the instrumental parts. "Raspberry Man" is a wryly funny sung-

spoken story that skillfully combines modern chamber music compositional style with an amusing

story about a fellow who stood outside Jack Dempsey's Restaurant in Manhattan and gave passers-

by the raspberries.

The second short piece, "Emmanuel Changed" has a similar trajectory.

It's interesting, funny, well performed and well written music with a definite twist.